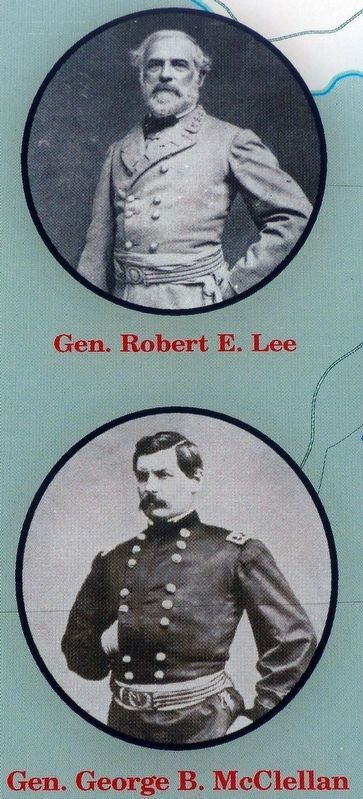

On the eve of September 16, 1862, two armies prepare for battle near the small town of Sharpsburg, Maryland. General Robert E. Lee's army invaded Maryland earlier in the month with the hope of winning the state for the Confederacy, demoralizing the Union, and perhaps gaining European recognition in the bargain. The invasion hasn't gone as Lee planned, but he decides not to give up without a fight. He has 21,000 men to General George B. McClellan's 60,000, but reinforcements are on the way. Tomorrow, September 17, Lee's army will stand against the Union.

McClellan has been studying Lee's numbers and positions for two days. Despite his careful reconnaissance, McClellan reports to Washington a gigantic Rebel army "amounting to not less than 120,000 men," outnumbering his own army "by at least twenty-five per cent." He's commanded the Union army for nearly a year, but this will be the first and last time he'll command his army in battle on this scale.

Confederate General Lafayette McLaws marches his hungry, weary men to Sharpsburg during the night, losing about a third of his force to straggling. They arrive before daylight, bringing Lee's force to about 35,000 men. The armies are ready as they'll ever be...

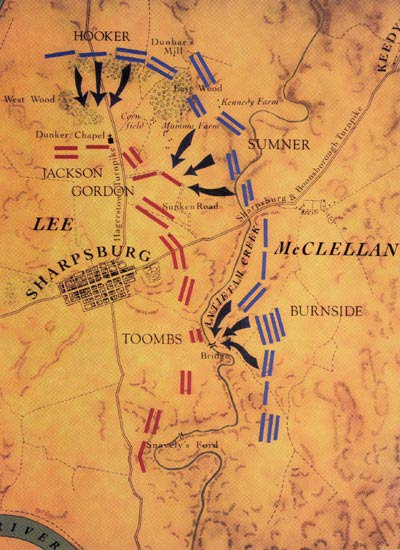

The battle begins at first light of morning with an attack from General Joseph Hooker's Union First Corps, heading south against Lee's left flank toward the Dunker Church. The troops face heavy resistance from General "Stonewall" Jackson's forces. Just as Union troops begin to make progress, they're driven back by General John Bell Hood's powerful counterattack. Assisted by Twelfth Corps reinforcements, Union forces finally make it to the Dunker Church and hold a position deep within Confederate lines, but a Confederate counterattack in the West Woods and other factors convince McClellan to stand firm where he is.

It's mid-morning and fighting has shifted south, where veteran Confederate troops under General D.H. Hill hold a defensive position in a sunken road. When Union soldiers under General William "Blinky" French attack, 1,700 of them are killed and wounded before reinforcements arrive. At 10:30 am, French's division is reinforced by General Israel Richardson, and Lee sends the last of his local reserves under General Richard H. Anderson.

Amid the chaos and bloodshed, Union forces gain a position that allows them to shoot down the sunken road. An officer accidentally shouts, "about face" and the Confederates begin to fall back, weakening Lee's center. With horrendous Union casualties, small but desperate Confederate counterattacks and the wounding of General Richardson, Union troops are on the defensive here as well. Some 5,600 men have been killed, wounded, or captured at what will come to be known as the Bloody Lane.

By 1:30 pm, the battle has claimed 17,500 casualties. But it's not over...

While the battle has been raging west of Antietam Creek, General Ambrose Burnside has waited sullenly on the creek's east side for General George McClellan's permission to enter the fray. Finally, the order arrives, and Burnside sets about getting his men across the water. He plans to force a crossing with most of his troops at a stone bridge and send the remainder to cross at a ford downstream. After two attempts to cross the bridge under close-range enemy fire, the third one succeeds. Now, 10,000 men cross the bottleneck. It takes them 2 hours.

Around 3 p.m., the bulk of Burnside's men are across the creek. Burnside makes strong progress against Lee's right flank until suddenly, seemingly out of nowhere, Confederate General A.P. Hill's "Light Division" emerges on the Union left flank and rear. Hill's men have charged directly into battle after marching 17 miles from Harper's Ferry. At that moment, Burnside is on the cusp of victory; he has the spires of Sharpsburg in his sights, but with his forces in danger, he pulls back to the bridge — a bridge that will forever bear his name. By sunset, some 23,000 men are casualties of this single day of fighting. 3,654 Americans are dead — more than at Pearl Harbor, on D-Day, or on 9/11.

Both armies tend their wounded, consolidate their lines and skirmish through the following day. McClellan writes to his wife, "Those in whose judgment I rely tell me that I fought the battle splendidly & that it was a masterpiece of art." The night of the 18th, Lee's army retreats across the Potomac River to Virginia. While the Battle of Antietam is considered a draw from a military point of view, it gives President Lincoln the "victory" he needs to deliver the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, setting the United States on the path to "a new birth of freedom."